The process begins when you identify a problem: the kitchen lacks storage, the house is too dark, the kids need a place to play that isn’t underfoot, you know you want to stay in your home as long as you can as you age but is that possible?

Eventually, you decide you want to find an architect to help you out. You call a few you found online or who were recommended by friends or associates. They either come by your home to meet you and see the problem or you go to their offices. They will show you their portfolios and listen to you describe your problem. They will then go away and write a proposal describing their understanding of your problem, what they can do to help, how much it will cost you and how long it will take.

Based on this information and your impressions of them, you select an architect and sign an agreement. The agreement may be and AIA (American Institute of Architects) standard document, or it might be something they have written. Ensure that their understanding of your problem and their description of what they will do coincides with yours. Generally, I use a contract that I have written that is based on various documents that I have used over the years. On a large project, I will probably break out the AIA documents.

The exact process will vary from architect to architect and on the size of the project. And my process will vary depending on the size of the project, my scope of services and the schedule. Design is not a linear process. We don’t start at A and proceed to B, then to C, on to D and so on ending up, inevitably at Z.

Design is more cyclical. We do indeed start at A and proceed to B, then to C, but we may cycle back to B again before proceeding on to D and then cycle back to C before moving on to E, and so on until we end up at either Z or X or 8 or some other destination we did not foresee at the beginning of the process. The more complex the problem, the longer this can take. And, frankly, design as an art form and expression of your and your architects aesthetic sensibilities often doesn’t happen on demand. It may take a few days or weeks wrestling with the problem before the seed of a solution is planted.

In spite of this reality, most projects will be divided into six phases:

Pre-design: identifying the nature of the problem and everything that needs to be taken into account

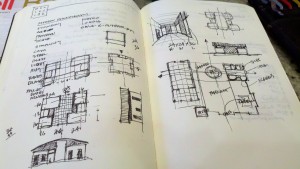

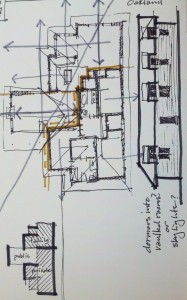

Schematic Design: using the program to develop diagrams of ways the problem could be solved, then testing the diagrams to see how they work as building plans

Design Development: taking the selected design and developing it in more detail to understand how it works and what it looks like

Construction Documents: developing the design further in a detailed way to describe to the builder and the building officials how the design might be built

Permit and Bidding: allowing the municipality to review the design for compliance with building codes and one or more builders to review the design to develop a bid. I prefer to bring in a builder earlier so they can help us control the costs and address construction issues before this point in the project.

Construction: building the solution

Some of these phases can be combined or eliminated based on the size of the project, but basically, all of these things will happen in the course of one project taken to completion. Some services I provide, like Design Counseling or “Aging at home” Consulting are usually quick combinations of the first two phases. I’ve recorded a short video about the phases of a typical project.

In an ideal world the cyclical nature of the design process slows significantly at the end of Design Development. In reality, it often continues into Construction Documents. In some cases it will continue right through Construction, which can be a boon or a detriment depending on the schedule and the budget.

Getting a project built can be like an epic journey, a noble quest that can be thwarted, seemingly at every turn, by the bureaucratic processes imposed by planning and building departments of the city or county where your project is. Most municipalities have their own review processes that may or may not require separate approvals by the planning department, building department, fire department, public works department, and even the health department. Each department will have it’s own internal process and requirements and approval for a seemingly simple addition can take anywhere from 2 months to 2 years or more depending on the jurisdiction.

Once the project is approved by all the relevant jurisdictions, then it will take far longer than you expect to see it built. Schedules can be affected by how busy the builders are, by weather, by availability of materials, realities of construction (concrete needs to cure, in small spaces you can’t have too many guys building at one time, etc.), delays caused by having to wait for inspections, and so on.

But it is all worth it when it’s done. The problem is solved and your life is, hopefully, improved! If all goes well, and it usually does, you, your architect and your builder will all be pleased with the results. That is my goal on all my projects.